The 15-minutes city: Utopia or dystopia?

Daily travelling has negative consequences on people’s well-being and the environment

The Covid-19 pandemic accelerated the shift towards remote work, with many individuals required to stay home to curb the spread of the disease. A survey of over 32,000 employees from various countries revealed that around two-thirds of the global workforce would consider finding a new job if their employer insisted on full-time office work. Flexibility has become a crucial aspect of employee well-being.

According to a study by the agency Digital.com, saving time and money on commuting ranks as the second most important reason for employees hesitating to return to the office, almost on par with childcare responsibilities. On average, EU citizens spent 25 minutes commuting one way in 2019, amounting to 9 to 10 full days annually. Lengthy commutes correlate with lower job and leisure satisfaction, increased strain, and poorer mental health.

When we add daily travel for leisure and school, it is not hard to understand why private transport contributes to more than 40% of the transport sector’s greenhouse gas emissions when 98% of passenger cars are powered by fossil fuels.

To address these challenges, solutions focusing on reducing daily travel time and individual carbon emissions are crucial. The “15-minute city” allows us to do both.

The 15-minute city, a recent but popular concept

The concept of the 15-minute city, introduced by French urbanist Carlos Moreno in 2016, promotes accessibility to all essential amenities within a 15-minute biking or walking distance. This includes shops, schools, healthcare, green spaces, restaurants, and cultural institutions, all within the same neighbourhood.

While it may seem idealistic amid rapid urbanization, particularly in developing countries such as Nigeria or Sri Lanka, where average commute times can be as long as one hour, the benefits are significant. 15-minute cities foster social interaction, reduce loneliness, decrease reliance on cars, create more space for cyclists and pedestrians, ensure safe pathways for vulnerable groups, and provide places for community engagement.

The concept gained global attention when Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo incorporated it into her reelection campaign and initiated its implementation during the pandemic, inspiring many cities worldwide to follow suit.

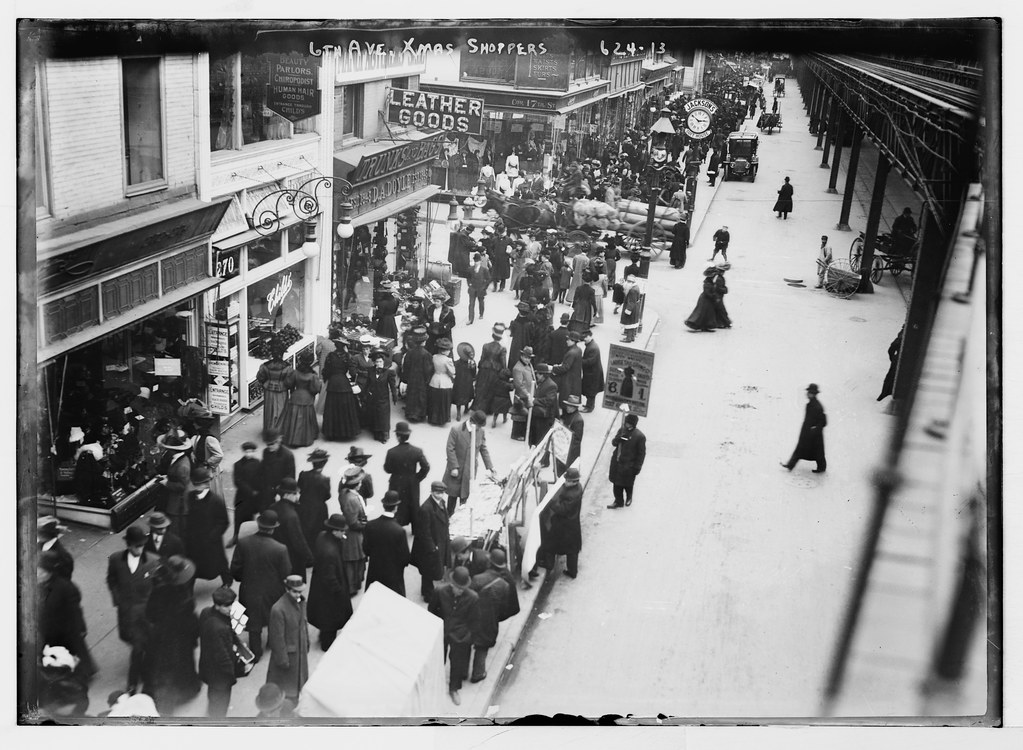

A need for walkability that came with the first cars

Walkable neighbourhoods were once a necessity, as walking was the most accessible transportation mode. But the rise of car usage gradually reduced space for pedestrians, often endangering human lives. This was one of the main reasons for several movements promoting walkability, cyclability and proximity of amenities to emerge, such as the “neighboring units” in the 1930s and New Urbanism in the 1980s. Amsterdam and other Dutch cities became walkable and bicycle-friendly through protests advocating for secure cycling infrastructure in order to prevent casualties, especially child fatalities.

Today, cities worldwide are implementing variations of these ideas. The Seaside neighbourhood in the US, featured in The Truman Show, showcases New Urbanism principles. Portland and Melbourne pioneered 20-minute neighbourhoods, similar to the 15-minute city concept (but excluding the commute to work). Barcelona, Paris, and Ottawa are actively reshaping their cities into 15-minute cities by leveraging existing infrastructure to provide convenient access to essential amenities. Notably, the “15-minute city” movement extends beyond Western countries, with Shanghai and other Chinese cities adopting similar ideas known as “15-minute communities” or “15-minute life circles.”

A concept that attracts criticism despite its popularity among urban planners

Implementing 15-minute cities has its challenges. The concept requires addressing extensive urban sprawl caused by car ownership. Ancient cities with established infrastructure may find it easier to adopt these plans compared to cities like Melbourne, which have to rely heavily on public transport.

Additionally, for every neighbourhood to have accessible amenities like healthcare, libraries, and parks, higher population density and smaller individual properties are required. This may mean sacrificing private gardens and forest walks in favour of balcony plants and public park strolls.

However, the risks associated with 15-minute cities extend beyond reduced private space. In the 1940s, neighbourhood units were criticized for facilitating the segregation of different racial, religious, ethnic, and economic groups by private developers. The fear of gentrification and displacement of lower-income residents due to rising property values remains relevant today. That’s why it is crucial for cities to incorporate accessible housing into their plans to avoid potential failures.

The potential impact on employment and economic disparities is another concern. Matthew McCartney highlights that, for workers, focusing on finding a job in a specific area may limit occupational choices, and depending on their “urban bubble”, it could influence their access to amenities, housing prices, and income.

Balancing the convenience and benefits of a 15-minute city with the potential risks requires careful planning to ensure inclusivity and accessibility. It demands a comprehensive approach that considers housing affordability, employment opportunities, and the overall well-being of diverse populations within the urban fabric.

Can these 15-minute neighbourhoods extend outside the cities?

Achieving 15-minute cities is unlikely, even in countries like France where laws imposing the presence of some amenities exist. Walkability is often high in urban areas, but walking or biking to school or supermarkets is often dangerous or impossible in rural regions.

To make 15-minute cities a reality, there must be a significant increase in amenities like food stores, medical services, cultural sites, and walk/cycle paths, but also work opportunities. This could require unprecedented levels of public funding and even public debt.

But these initiatives shouldn’t be rejected all because of their high cost. They represent an ideal society where big cities aren’t associated with loneliness and long commutes, and small villages aren’t limited by cars and distant hospitals.

While striving for 15-minute cities, we offer carpooling as an alternative to enhance neighbour relationships and reduce commuting time and carbon emissions. Complementarity, not competition, is essential for addressing challenges and creating a greener and more enjoyable world.

Let’s work towards these goals, understanding that even if we fall short of reaching the moon, we may still land among the stars.